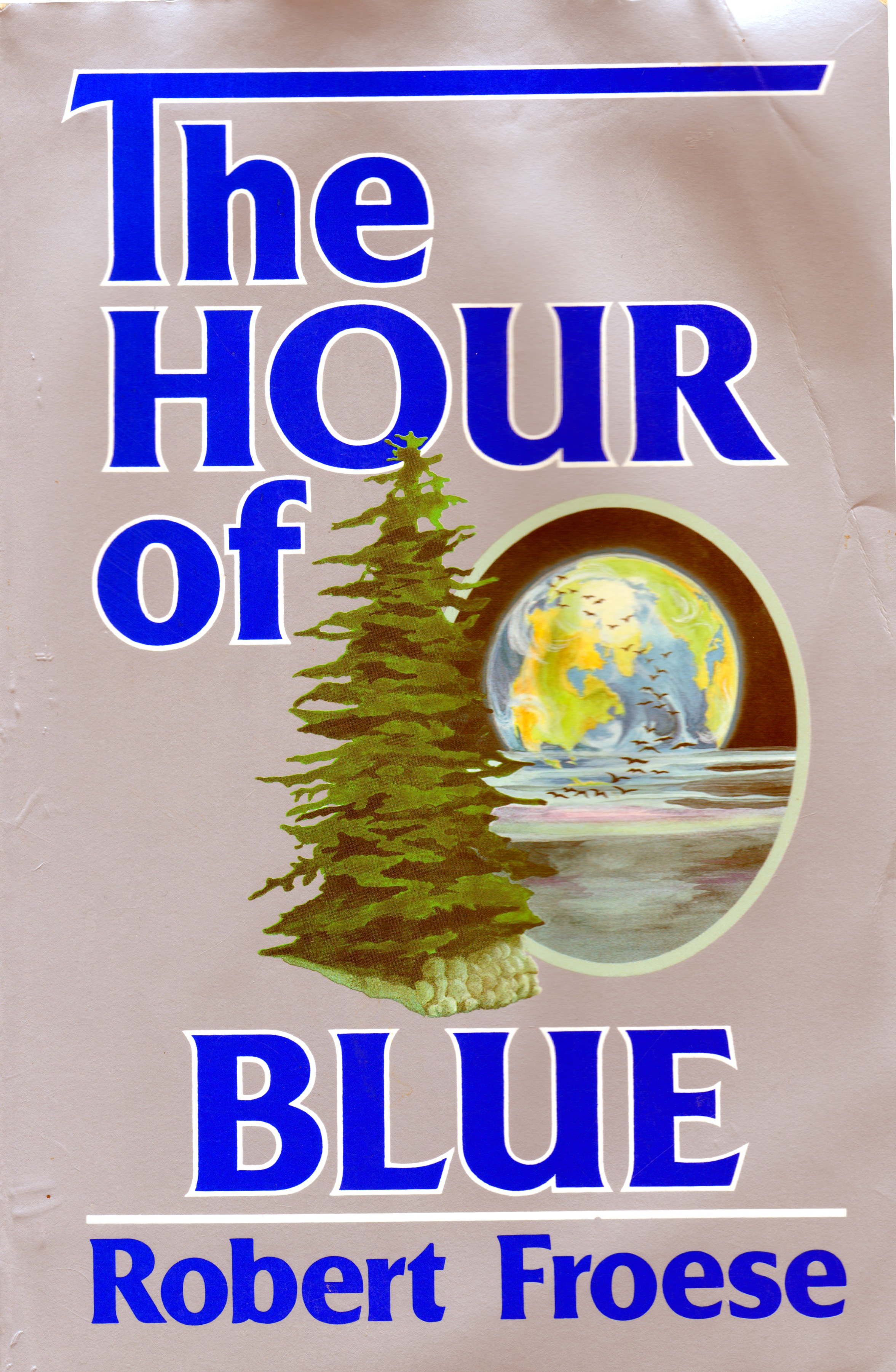

The Hour of Blue

There are warnings—some subtle, some not. Dolphins communicate signals of alarm. Unusual children talk to birds and speak of wind on the moon. The setting—the forested coast of Maine. The backdrop—global environmental crisis.

Amos Thibault, computer expert with Maine’s Forest Service, is puzzled by satellite data he’s been gathering for a real-time forest inventory. The forest, he discovers, is inexplicably changing. And at Penobscook Bay, where the changes appear to be focused, he finds more: the woman whose studies of dolphin communications have drawn her to the same bay, the school of children with special talents, and the man in the three-piece suit, super-developer John Furst, with his grand plans for Maine’s forest and coast.

The answer to the deepening mystery lies with a strange trio of medical researchers, whose activities finally unveil the principal player in the drama: the Earth itself. As a frightening epidemic of catatonia spreads among local residents, all are eventually caught up in the growing puzzle. Earth has been awakened, and a night of transformation is at hand. The world will never be the same.

Based on the Gaia Hypothesis—that Earth is a living thing, a massive, complex, and sensitive organism—The Hour of Blue suggests that Earth may also be capable of protecting itself—but not without consequence for those who would hurt it. The novel combines science fiction, suspense, and the environmental issues of today. Its haunting message is both a warning and a statement of hope.

At the moment, it’s raining in the forest. Or anyway it’s dripping. Up there above the taller trees, it may have stopped raining hours ago—sometimes it’s difficult to tell.

A lot of people would call this jungle. Which is a word better for fantasy, loincloth romance, as far as I’m concerned. I prefer forest—a place defined by trees. That’s the way it is here, the trees are everything. Underneath, the soil lies thin, not as fertile as you'd think for all that grows. Overhead, the climate rages, but the wind never touches the soil, and water reaches it only by seeping and dripping through the layers of canopy above. Lush as the place is, without the trees the rest of it would vanish, turn to grass and rock.

Much of the time now, during wet season, I wait inside this tent the color of the sea. The tent walls are moist, luminous, turning everything aquamarine and brightening the color of my skin. It’s a shade soothing to the eyes, good for daydreaming. I’ve grown used to living in this tent. I drink strong coffee, eat fourteen varieties of fruit, and wear clothes badly stained by mildew.

Clouds roll over this region of Earth just as elsewhere, but you have to climb out of the valley or trek down to the river to see them. They are disconcerting clouds—ragged, hungry—though we've discovered their chemistry is more elemental, not so poisonous as back home. Of course, all that is changing.

As always, the trees are under surveillance. They are marked and, according to the latest government plan, will be put to use. I remember X telling me that certain rare lubricants in our satellites come from the trees in these forests. But that isn’t why men cut them down. The men are after paper. And land to grow bananas.

It doesn’t matter how deep into the forest you go. You can travel for days. You listen and you can hear them. The saws, the bulldozers, chewing up the forest. The way you do it—you put both hands on the trunk of a sapucaia, your ear to the soft bark, and squeeze. The sound pours out like honey. You can hear them. It sounds crazy, I know. But it’s true. I learned it from Amelia, the molecular-biologist sorceress. She’s expert at that sort of thing.

What most startled me here at first were the insects—the size birds, some of them, and colorful. Like robotic specimens of folk art, they move through the forest on legs and wings in kaleidoscopic orbits, buzzing, searching for things to devour: plants mostly, or one another. However, one tiny species of fly here hovers outside the tents and in ambush along the trails. If it catches you in an unguarded moment, it will dart in and drink the fluid on the surface of your eye. When this happens, you see only a Shadow and feel nothing. The little fly is as fast as it has to be and can avoid blinking eyelids like a child jumping rope. It is harmless, but there are other species deadly poisonous. Some of them very beautiful. One learns to live by such congruences. Death and beauty, in exquisite combination.

This rain forest, our refuge, has for a time become our world. We have nothing to complain about. We walk the trails, venture into broadleaf vegetation lugging recorders and microscopes, like gigantic and erudite ants, foraging for information. Rose-lighted evenings around rude tables we dine quietly on roots and beetles and nectar, and afterward bathe in the river. A part of the weave now. It is more than enough for us, this world.

And now, as if we needed the excitement, it is a world at war.

Again this morning we were awakened by helicopters, the seventh morning in a row. Always around dawn, the hammering whir that seems as if it couldn't get any louder, though it always does. All the more menacing when you can't see the sky.

By some romantic twist, they call themselves Air Cavalry. The mechanized mounts of the beige police. The hounds of hell, Amelia calls them. Dropping canisters, gas, incendiaries—burning hillsides, valleys. All, incredibly, in pursuit of us. What do they imagine they’re accomplishing?

Every week, out spurts another expedition. Search units, they’re called. They sweep eagerly after us down networks of trails, unsuspecting, hurried along in file as if by peristalsis, to disappear, dissolve in vegetation like so many granules of light brown sugar in the lining of some vast green stomach. They have no idea what they’re up against, what it is they’ve declared war against.

Even now, sometimes, I wonder at my being here. Working, hiding in another land, an outlaw in my own. Though, certainly, my situation is incidental, unimportant. What matters is this thing that is happening, this new thing that has come to the world, pouring over it like a song. Arising from the forest floor to neutralize the metal air of cities.

Think of it as a transformation.

Or, better, as the correction of an error.

An erasure.